The Hidden Value of the Backward Pass

- J. M. García de Marina

- Dec 23, 2025

- 6 min read

Why going backwards is often the most progressive decision in football

Few actions in football are judged as harshly as the backward pass. It is booed in stadiums, criticised in television analysis, and quietly penalised in most analytical models. When a team plays backwards, the dominant interpretation is almost automatic: they are afraid, they lack ideas, they are wasting time.

Modern football analytics, despite its sophistication, has largely inherited this intuition. Most possession-value frameworks reward territorial gain, verticality, and immediate threat. Backward passes, by definition, move away from goal and therefore tend to receive low or negative instantaneous value.

This article argues that such an evaluation is structurally incomplete.

Backward passes are not designed to create value immediately. They are designed to change the conditions under which the next actions will occur. Judging them only by their immediate output is like judging a chess move solely by whether it captures a piece.

The central question here is not what does a backward pass do now? It is:

What does a backward pass make possible next?

Football is sequential, not atomic

Most analytical models implicitly treat football as a chain of independent actions. Each event is evaluated in isolation, assigned a value, and summed across a match or a season.

This approach works well for shots, crosses, and final passes. It works poorly for actions whose primary function is structural rather than terminal.

Backward passes belong firmly in this second category.

They often exist to:

reset the attacking shape,

move the defensive block,

improve spacing between lines,

create a superior angle for the next progression.

These effects do not show up in the moment the ball is played backwards. They appear one, two, or three actions later.

If analysis stops too early, it systematically mislabels enabling actions as unproductive ones.

Why instantaneous metrics fail backward passes

To understand the problem, consider how most value models operate.

Whether xT, VAEP-style frameworks, or custom possession value models, they typically answer some variant of the same question:

Given the state of the game before and after this action, how did the probability of scoring change?

Backward passes almost always fail this test. They:

reduce proximity to goal,

lower immediate xT,

and rarely lead directly to shots.

But this logic assumes that value must be created instantly to exist at all.

In reality, many high-quality attacks begin with actions that appear negative in isolation:

a centre-back recycling possession,

a midfielder dropping the ball off to a fullback,

a forward laying the ball backwards under pressure.

The value of these actions lies not in what they achieve directly, but in how they reshape the game state.

A different question: what happens after?

Instead of evaluating backward passes at the moment they occur, this analysis evaluates them by what follows.

The conceptual shift is simple but fundamental:

Do not ask whether the backward pass was valuable.

Ask whether the sequence that followed was.

If a backward pass consistently precedes sequences in which the team creates danger, then dismissing it as “negative” is analytically unjustified.

Crucially, this perspective does not require tracking data. It requires only two ingredients:

event timestamps,

a per-action offensive value metric (here, DOV).

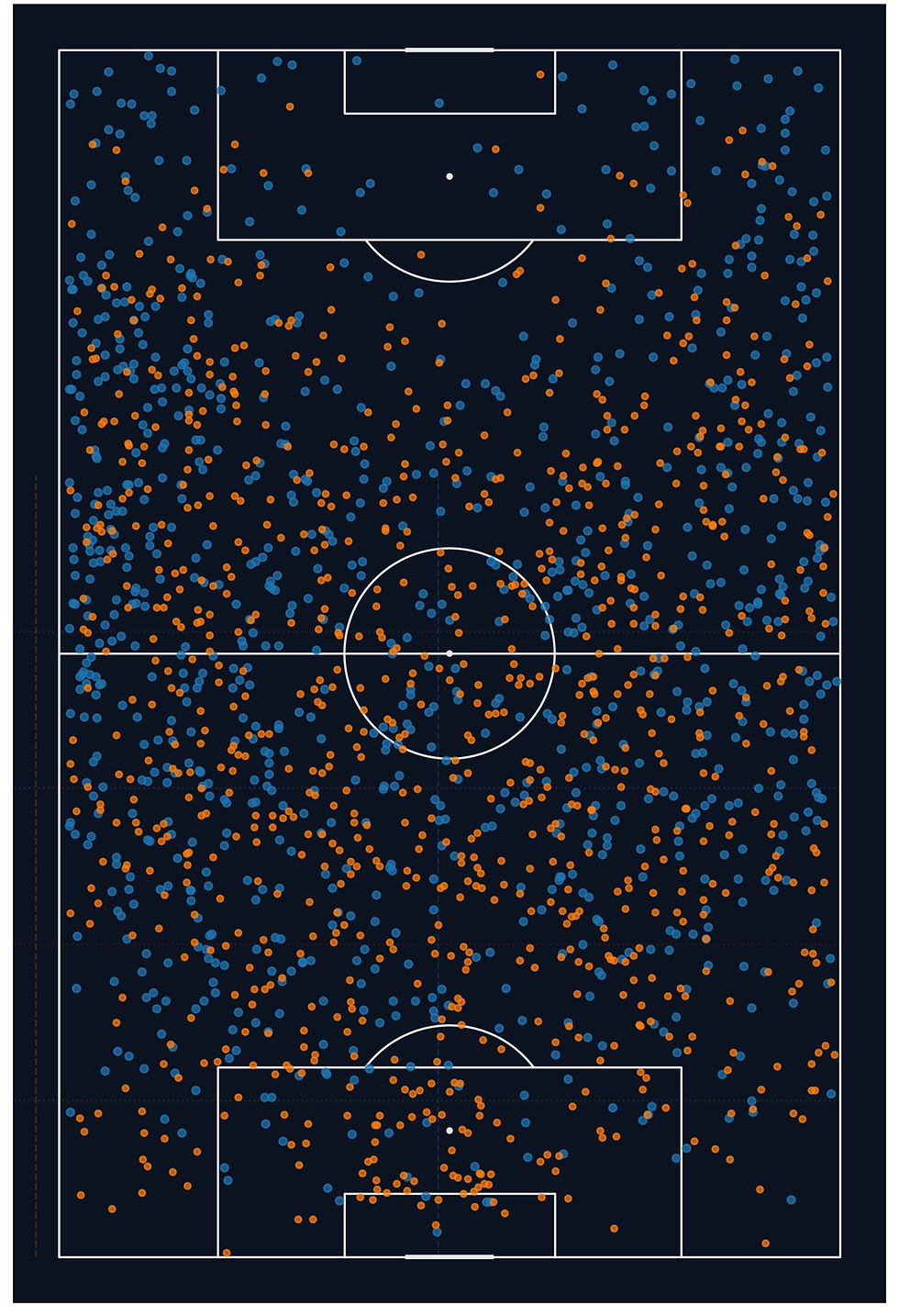

Defining the backward pass

To avoid subjective interpretation, the definition is deliberately strict.

A backward pass is any pass where:

the ball’s end location is meaningfully further from the opponent’s goal than its start location,

excluding clearances and emergency long balls.

The goal is not to capture every “recycling” action, but to isolate passes whose intent is clearly non-progressive in the moment.

These passes are then compared not to progressive passes — which would be a strawman — but to lateral passes from similar zones. This control group is essential. It ensures that any observed difference is not simply a function of safety or possession retention, but of directional choice.

Measuring future value: the core idea

For each backward pass played at time t0t_0t0, we observe the team’s actions over short, fixed time windows:

3 seconds,

5 seconds,

10 seconds.

Within each window, we sum the offensive value (DOV) generated by the same team.

The sequence is immediately terminated if possession is lost. This prevents artificially inflating value through unrelated phases of play and preserves causal plausibility.

This quantity is called Future DOV Gain (FDG).

It represents the amount of offensive value the team generates after playing a backward pass, before anything external interrupts the sequence.

Importantly, this does not claim that the backward pass caused every subsequent action. It claims something more modest and more defensible: that the backward pass enabled a sequence in which value was created.

Why short windows matter

The choice of short time horizons is deliberate.

Long windows blur causality. Very short windows miss structural effects. The 3–10 second range captures the period in which:

the defensive block reacts,

the attacking team reorganises,

and the next meaningful progression is attempted.

Empirically, results are stable across this range. Conceptually, it aligns with how coaches think about phases: not as minutes, but as moments.

What emerges from the data

Once backward passes are evaluated through FDG rather than instantaneous value, several patterns become visible.

1. Backward passes are not neutral

On average, backward passes generate non-trivial future offensive value. In many zones — particularly deep central areas and half-spaces — they outperform lateral passes from the same locations when measured over 5–10 seconds.

This does not mean backward passes are universally good. It means they are context-dependent, not inherently negative.

2. The value is delayed

At 3 seconds, backward and lateral passes often look similar.At 10 seconds, differences become clearer.

This temporal profile matters. Models that stop too early systematically miss the payoff of structural actions.

Backward passes are rarely about the next touch. They are about the one after that.

3. Player profiles diverge sharply

Some players play many backward passes with low FDG. Others play fewer, but consistently generate high future value.

This distinction is invisible if analysis stops at pass counts or completion rates. It becomes obvious when sequences are considered.

These players are not conservative. They are architects of tempo and structure.

Tactical interpretation: backward passes as structural tools

From a tactical perspective, backward passes with high FDG tend to share certain characteristics.

They often:

precede switches of play,

move the defensive block horizontally,

create space for third-man runs,

allow a new angle of progression to emerge.

In this sense, they function as tempo-reset mechanisms.

They slow the game down briefly in order to speed it up more effectively afterwards.

This is not passivity. It is control.

The difference between a good and a bad backward pass

The analysis does not claim that all backward passes are valuable. Far from it.

Many backward passes generate little or no future value. These are typically:

played under panic,

disconnected from the team’s structure,

or used simply to avoid risk.

The key insight is that backward passes are not equal.

What distinguishes the good ones is not direction, but what they enable.

A backward pass that leads nowhere is wasteful.A backward pass that reopens the game is progressive in the deepest sense of the word.

Addressing common objections

“Isn’t this just rewarding possession for its own sake?” No. Time alone is irrelevant. Only offensive value is counted, and sequences end immediately at possession loss.

“Couldn’t any safe pass look good in this framework?” No. Lateral passes from the same zones form the control group, and many of them generate little future value.

“Isn’t the time window arbitrary?” Yes — intentionally. The stability of results across multiple short windows is precisely what strengthens the argument.

Why this matters for analysis and coaching

This approach has several practical implications.

For analysts, it highlights a blind spot in many evaluation pipelines: structural actions are undervalued because their payoff is delayed.

For coaches, it provides a language to differentiate between:

sterile recycling,

and purposeful resetting.

For recruitment and player evaluation, it identifies profiles that traditional metrics systematically miss: players who improve the conditions of attack rather than its immediate output.

Most importantly, it forces a conceptual correction.

A broader lesson

The backward pass is only one example.

The deeper lesson is methodological:

Football actions cannot be fully understood in isolation.Their meaning emerges in sequence.

Any model that ignores short-term future context will systematically misclassify enabling actions as unproductive ones.

Backward passes simply make this flaw impossible to ignore.

Conclusion: redefining progression

Progression in football is often described spatially: moving the ball closer to goal. In reality, progression is conditional: moving the game toward a state in which danger can be created.

Backward passes, when used intelligently, do exactly that.

They are not conservative by default.They are investments in future structure.

When evaluated through sequences rather than snapshots, many backward passes emerge not as the enemy of attacking football, but as one of its most misunderstood tools.

Comments